PEW Report on Income Mobility

PEW reports on Income Mobility

The mobility from the bottom is better in the US, but not as high as some would wish.

However the assessment of what number for mobility is good is not clear. If the absolute mobility upward of all quintiles, more in the US than most other diverse, developed countries, is high how is this taken into consideration?

Given the increase in the number of households since the 60's, usually in the bottom quintile, the upward mobility is certainly worth noting, for 60% in the bottom quintile make it out.

40% of offspring tend to follow their parents, unless

forces propel them up or down.

Links:

Income Mobility

Rich or Poor: Reason report

Congress on Mobility

Mobility before 1996

Mobility from 1980

Mobility from 1995 to 2005

Middle Class: effects on mobility

Treasury Report on Mobility

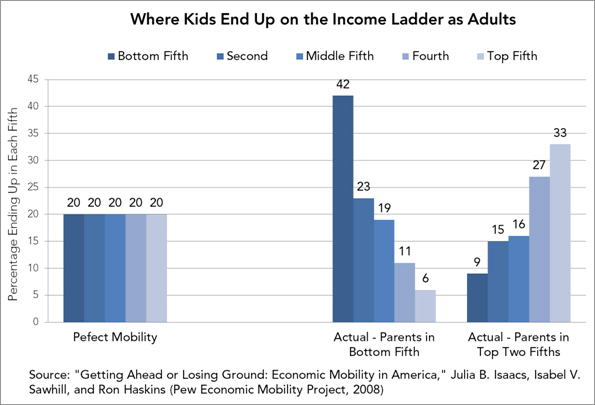

The EMP/Brookings analyses break the parent and child generations

into fifths on the basis of each generation’s income distribution. If

being raised in the bottom fifth were not at a disadvantage and

socioeconomic outcomes were random, we would expect to see 20 percent of

Americans who started in the bottom fifth remain there as adults, while

20 percent would end up in each of the other fifths. Instead, about 40

percent are unable to escape the bottom fifth.[6]

The EMP/Brookings analyses break the parent and child generations

into fifths on the basis of each generation’s income distribution. If

being raised in the bottom fifth were not at a disadvantage and

socioeconomic outcomes were random, we would expect to see 20 percent of

Americans who started in the bottom fifth remain there as adults, while

20 percent would end up in each of the other fifths. Instead, about 40

percent are unable to escape the bottom fifth.[6]

This trend holds true for other measures of mobility: About 40 percent of men will end up in low-skill work if their fathers had similar jobs, and about 40 percent will end up in the bottom fifth of family wealth (as opposed to income) if that’s where their parents were.[7]

Is 40 percent a good or a bad number?

On first reflection, it may seem impressive that 60 percent of those starting out in the bottom make it out. But most of them do not make it far out. Only a third make it to the top three fifths. Whether this is a level of upward mobility with which we should be satisfied is a question usefully approached by way of the following thought experiment: If you’re reading this essay, chances are pretty good that your household income puts you in one of the top two fifths, or that you can expect to be there at age 40. (We’re talking about roughly $90,000 for an entire household.) How would you feel about your child’s having only a 17 percent chance of achieving the equivalent status as an adult? That’s how many kids with parents in the bottom fifth around 1970 made it to the top two-fifths by the early 2000s.[8] In fact, if the last generation is any guide, your child growing up in the top two-fifths today will have a 60 percent chance of being in the top two fifths as an adult. That’s the impact of picking the right parents — increasing the chances of ending up middle- to upper-middle class by a factor of three or four.

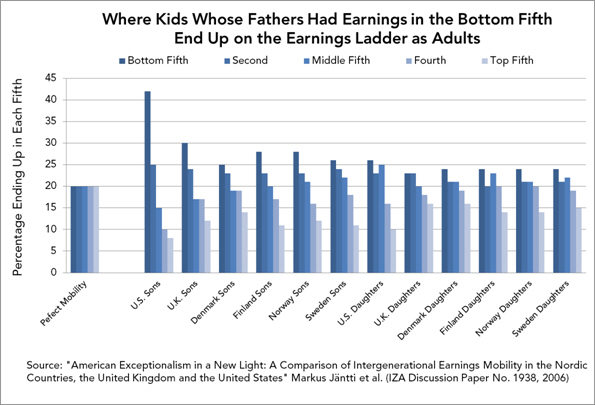

Comparisons with other nations can also be helpful, though

interpreting the evidence is surprisingly tricky. Research shows that

most Western European and English-speaking nations have higher rates of

mobility than does the United States. Cross-national studies of mobility

typically consider the “intergenerational elasticity” of earnings — the

amount of additional earnings that an extra 10 percent in parental

earnings buys children in adulthood.

Comparisons with other nations can also be helpful, though

interpreting the evidence is surprisingly tricky. Research shows that

most Western European and English-speaking nations have higher rates of

mobility than does the United States. Cross-national studies of mobility

typically consider the “intergenerational elasticity” of earnings — the

amount of additional earnings that an extra 10 percent in parental

earnings buys children in adulthood.

By this third way of measuring mobility, we are definitely worse off than Canada, Australia, and the Nordic countries, and probably worse off than Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[9]

An easy way to characterize how bad we look is to compare ourselves with our neighbors to the north. In Canada, a boy whose father earns twice as much as his friend’s dad can expect to have about 25 percent more in earnings as an adult than his friend. In the United States, he’ll have on average 60 percent more.[10]

What is clear is that in at least one regard American mobility is exceptional: not in terms of downward mobility from the middle or from the top, and not in terms of upward mobility from the middle — rather, where we stand out is in our limited upward mobility from the bottom.

What is clear is that in at least one regard American mobility is

exceptional: not in terms of downward mobility from the middle or from

the top, and not in terms of upward mobility from the middle — rather,

where we stand out is in our limited upward mobility from the bottom.

And in particular, it’s American men who fare worse than their counterparts in other countries.[16] One study compared the United States with Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the United Kingdom. It found that in each country, whether looking at sons or at daughters, 23 to 30 percent of children whose fathers were in the bottom fifth of earnings remained in the bottom fifth themselves as adults — except in the United States, where 42 percent of sons remained there.[17]

Cross-national surveys show that Americans are more likely to believe they live in a meritocracy than are residents of other Western nations.[18] When told in an EMP poll that Sweden and Canada have more mobility than the United States, just four in ten said it was a major problem.[19] One explanation for this finding is that high living standards and levels of absolute mobility make relative mobility of secondary concern for Americans. Indeed, EMP polling indicates that an overwhelming 82 percent prioritize financial stability — keeping what they have — over “moving up the income ladder.”[20] In that case, tending to the American Dream demands that policymakers work to promote absolute upward mobility.

But Americans across the ideological spectrum are unhappy with the lack of relative upward mobility out of the bottom.

When given the actual percentage of people stuck in the bottom, 53 percent of

Americans, and half of conservatives, deemed it a “major problem.”

Living up to our values therefore requires policymakers also to focus on increasing upward relative mobility from the bottom.

The most direct way to increase upward absolute mobility is with policies that promote strong economic growth, which in turn requires a focus on economic efficiency. But here relative mobility comes back in — because low relative mobility is inefficient. The mass of people stuck at the bottom is likely to represent an incredibly costly misallocation of human resources. Of course, one-fifth of the population has to be in the bottom fifth, but that quintile does not have to be filled so disproportionately with the children of disadvantaged parents. Many people in the bottom fifth are likely to have made the same bad choices as their parents before them. Different people will hold them more or less accountable for their shortcomings, and that is a major fault line of American politics.

Where to look to encourage more upward relative mobility?

Begin with the fact that just 16 percent of those who start at the bottom but graduate from college remain stuck at the bottom, compared with 45 percent of those who fail to get a college degree.[22] There is a legitimate debate about whether pushing academically marginal students into college will give them the same benefits that current college graduates receive, but there are surely financially constrained students who would enroll — or who would stay enrolled — if they could afford to.

Broad-based economic growth, international competitiveness, and the ideals composing the American Dream all require that policymakers heed Governor Daniels’s call. Increasing upward absolute mobility — for all, but with a particular focus on those who start out at the bottom — should be the primary goal of policymakers. The first political party that commits itself to putting upward mobility first and that credibly takes on the challenge will be ascendant.