Viewing history is often done through dark sunglasses so as not to see the truth:

The contradiction between stimulus Keynesian economics and higher tax rates should be apparent, but is only to those who see that the government is not a productivity machine. The Government does not enhance productivity nor economic growth as it proceeds to spend lavishly, regulate profusely, and assume it is doing good. It is a net drag in so many ways.

We often forget the lessons learned from history, and when politics take over the memory seems quite handicapped.

Obama's Revenue Soup A history lesson on capital gains taxes. Link

In "Annie Hall," Woody Allen tells the joke of two women complaining about a restaurant. The first says the food here is awful and the second replies, yes, and they serve such small portions. Sounds like President Obama's proposal to raise the capital-gains tax: It will hurt the economy and it won't raise much new revenue.

Mr. Obama's plan would raise the capital-gains rate on January 1 to 20% on those who earn more than $200,000 ($250,000 for couples), plus a 3.8% investment surtax to finance ObamaCare. That 23.8% rate amounts to a nearly 60% increase from the 15% rate in effect since 2003. And that's without his new "Buffett rule," which would take the rate to 30% for many taxpayers.

This and other rate hikes aimed at higher-income earners are supposed to raise about $700 billion in tax revenues over the next decade. Fat chance. Ever since the famous 1978 bipartisan capital-gains tax cut sponsored by the late William Steiger of Wisconsin, the same pattern has repeated itself: raising the capital-gains rate reduces revenues, and lowering it leads to revenue increases.

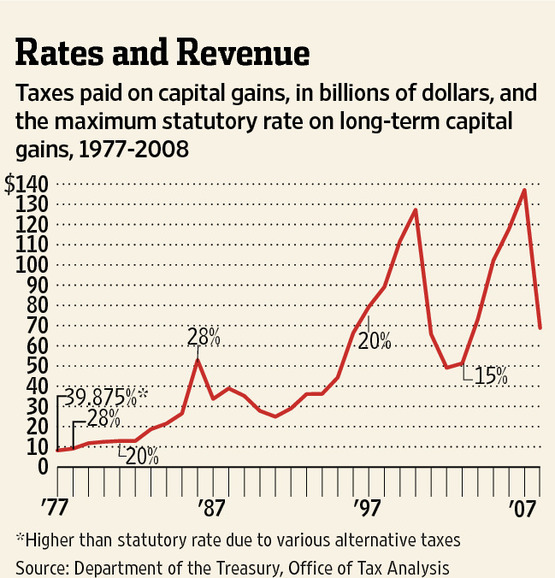

The nearby chart shows the 35-year trend in capital-gains revenue and tax rates—through 2008, the last year data are available. The Steiger amendment cut the top rate to 28% from nearly 40% in what was a watershed moment in U.S. tax policy and a preview of the Reagan era. Revenue from capital gains quickly jumped to $11.8 billion in 1979 from $9.1 billion the year before.

Congress cut the rate again in 1981 to 20% as part of the Reagan tax cuts, and the striking fact is that revenues didn't fall in 1982 despite the steep recession. By 1983 they were rising again, to $18.7 billion, and they kept rising along with the Reagan boom.

The next policy break came in 1986, when Congress returned the capital-gains rate to 28% as part of tax reform. A funny thing happened: Revenues soared in 1986 to $52.9 billion as investors cashed in their gains before the tax increase hit in 1987. But then revenues plunged, despite the higher tax rate, to $33.7 billion. They rose slightly in 1988 but then stayed flat for nearly another decade.

In 1997, Bill Clinton and the Gingrich Republicans cut the rate back to 20%, and revenues really took off—doubling to $127.3 billion in 2000 from $66.4 billion in 1996. These were also the years of a stock-market boom, and investors cashed in their gains along the way.

Capital-gains revenues fell amid the dot-com bust, but in 2003 George W. Bush and Republicans in Congress chopped the rate to 15%. Even at that lower rate revenues started to climb again (along with the economy), rising from $51.3 billion in 2003 to $137.1 billion in 2007. They understandably fell again in 2008 as the recession hit and stock values fell.

The data clearly show that the overall economy is the single biggest factor in capital-gains realizations and revenue. But the data also show that time and again revenue has multiplied despite a lower rate, and arguably because of it.

The capital-gains levy is an elective tax on owners of stock and other assets. Investors only pay the tax when they sell their assets, so they can hold unrealized gains until the tax rate falls. This is called the "lock-in effect" of high capital-gains tax rates. It reduces economic efficiency because at a higher tax rate capital hibernates in older companies with lower growth potential and isn't available to new ventures with higher returns. A higher capital-gains tax also makes equity ownership less valuable (because of the lower after-tax returns), so there is less appreciation in stock values when the tax rate is higher.

Congress shouldn't be fooled by government forecasters who predict a revenue boom from a higher capital-gains rate. They have blown this call every time. After Bill Clinton signed the 1997 cut, revenues came in about one-third higher than the government had predicted from 1997-99. The same thing happened with the 2003 rate cut. The government's forecasts of tax collections were too low for 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007. From 2005-2007 tax collections from capital gains were at least 40% higher than originally predicted.

In our view the optimal capital-gains tax rate is one that leads to the most capital investment, jobs and wealth gains for American workers. That economically optimal rate is somewhere close to zero and would lead to more overall tax revenue as the economy grew faster. But if Congress wants a capital-gains tax, history suggests the revenue maximizing rate is closer to 15% than to 23.8%.

As John F. Kennedy put it in 1963 when he endorsed a cut in this tax: "The tax on capital gains directly affects investment decisions, the mobility and flow of risk capital" as well as "the ease or difficulty experienced by new ventures in obtaining capital, and thereby the strength and potential for growth in the economy."

Today's Democrats in Washington are no Jack Kennedys. As President Obama told Charlie Gibson of ABC News in 2008, whether or not a higher capital-gains tax raises more revenue is irrelevant to him. He wants a higher rate as a matter of "fairness." The soup may be lousy but he wants more of it.

What do you make of these ideas?